The best way to fix a bad brief is to not write one in the first place. But stuff happens. Your first draft may be a clunker. That’s why it’s called a “first draft.”

So here is a checklist. Whether you look at it before you write a creative brief or after, keep these ideas in mind and you’ll put yourself on a path toward an inspired document for your creative team(s).

1. Always collaborate. Never write alone.

It’s a simple truth: two minds are better than one. Two is my ideal number, too. I like the idea of partnering with a colleague to write the creative brief. My first choice is to partner with a creative. If no one volunteers, it may be time to go recruiting.

A word of caution: Just because you partner with someone doesn’t guarantee your creative brief will always be inspired. Even art director/copywriter creative teams produce less than stellar advertising concepts. The work is only as good as the thinking that goes into it. Ditto for a creative brief.

Give yourself a head start by working with a colleague. You’ll have a sounding board. If you work with a creative, you’ll buy yourself a little extra credibility when you brief the creative team(s) with your brief because the creative department now has a bigger stake in the outcome. The upsides are numerous. The downsides are negligible.

Together, you and your collaborator have a much better chance of producing an inspired creative brief. And when creatives like a brief, they deliver better work. That helps everyone.

2. If your communication objectives aren’t clear, neither is the brief. Start your fix here.

There are lots of places where a creative brief can go wrong. While creatives tend to look first at the Single-Minded Proposition, you as the non-creative member of the creative brief-writing team should start by looking closely at the box labeled “Communications Objectives.” It may have a different label on your brief, such as “Reasons why we’re advertising” or “Purpose of the advertisement.” Whatever it’s called, this box is where everything begins, especially the Single-Minded Proposition (more on that next week).

Objectives are the facts of the creative brief. They tell the creative team what has to be accomplished by the communications they are creating. They don’t tell them the “why,” however.

Still, lack of clarity here produces impenetrable fog later.

3. How many objectives are listed?

If you have four or more, chances are you have too many. I think three is ideal, but you could have four if one of your objectives is “Reinforce the brand.” This is a foundational objective, meaning it always drives home the core message of the brand.

4. Are the objectives jargon free?

It is remarkably easy to slip in business lingo, marketing-ese, or insider-speak when you write a brief. It’s almost like a default language and you have to be on the look-out. You must be ever vigilant. Jargon kills an inspired creative brief. Always use clear, direct language, the kind you’d expect to read on your brand’s website or in an ad. Keep it simple!

5. Does each objective create a specific expectation?

For example, if one of your objectives is to “tell your best customer about how your brand cleans better…,” ask yourself if the word “tell” gives your creatives clear direction. Is that the strongest verb you can think of to accomplish this task?

The stronger your verbs in this box, the clearer the objective becomes. Could you say “excite your best customer…” or “persuade your best customer…” or “motivate your best customer…”? The right verb in the right place changes things dramatically. It’s a small thing with a big impact.

6. Have you chosen the right product benefits?

Most brands have a host of benefits, the reasons why a buyer could make an emotional connection to the brand. But only a select few benefits stand out as essential reasons to buy.

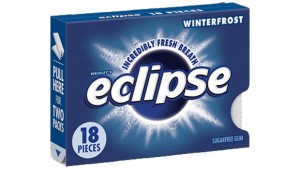

One example I like to use to illustrate this point is the brand of chewing gum I buy: Eclipse Winterfrost. I buy it because I like the taste. That would be it’s #1 feature. So what is the benefit of great taste? The obvious answer is: My breath is always fresh when I chew it so I feel confident.

But I also like the convenient size of each piece of gum and the handy dual 9-piece holders. The size of each piece of gum is a product feature. The benefit might be that the gum is easy to chew and doesn’t overwhelm my mouth. The two 9-piece holders are another product feature. Their benefit might be that I can easily carry them in my pocket.

Is either one, or both, truly a reason to buy this brand of gum? Perhaps, but I don’t think I’d want to create an entire ad around either of them. The benefits aren’t compelling enough. The feeling of confidence I get because I don’t have bad breath is more important.

Is either one, or both, truly a reason to buy this brand of gum? Perhaps, but I don’t think I’d want to create an entire ad around either of them. The benefits aren’t compelling enough. The feeling of confidence I get because I don’t have bad breath is more important.

So make sure the product features and their respective benefits correspond to a meaningful reason to buy. If you’re using the wrong benefits, or not the strongest benefits, your creative brief may not have credibility.

NEXT WEEK: How to fix a bad creative brief, Part 2—The Single-Minded Proposition