Basketball legend Kobe Bryant has made countless jump shots and layups in his practice sessions.

Basketball legend Kobe Bryant has made countless jump shots and layups in his practice sessions.

“As a kid growing up, I never skipped steps. I always worked on fundamentals because I know athleticism is fleeting.” Kobe Bryant

Tennis star Serena Williams has likely hit uncountable numbers of volleys in practice since she was a young girl. Someone asked if her success were due to luck.

“Luck has nothing to do with it, because I have spent many, many hours, countless hours, on the court working for my one moment in time, not knowing when it would come.”

The legendary golfer Jack Nicklaus has said that he played fewer tournaments than his fellow competitors because he chose to spend that time practicing his game at home.

“Nobody—but nobody—has ever become really proficient at golf without practice, without a lot of thinking and then hitting a lot of shots.” Jack Nicklaus

Seinfeld has told tens of thousands of jokes on stages across the country. Ballet star Misty Copeland has spent thousands of hours in the classroom, working at the ballet barre, all in preparation for her performances. Speaking legend Tony Robbins has rehearsed hours and hours for his presentations.

The same is true for ministers, gymnasts, coaches, courtroom lawyers…you name the profession, and you can imagine the almost unimaginable hours of preparation these dedicated individuals have devoted to their craft, all to be ready to display their skills when they matter most: on the job.

So I ask you: How much preparation have you put in to write a creative brief?

Here’s my guess: Exactly none.

There is no preparation. You just write one when you have to write one.

And therein lies a major missed opportunity. No one practices the skills required to write a creative brief well. There is no “creative brief boot camp” to make you sweat your tail off learning the fundamentals of writing this document. There should be.

Sounds absurd, right? Not from where I sat, which was on the receiving end of one of those too often poorly written documents that landed on my desk.

As a point of comparison, creatives constantly practice their concepting skills. Young creatives especially. Sometimes they don’t know when to stop practicing. They do “spec” work, whether it’s for their own professional portfolio or some pro-bono client or even a friend’s dog-sitting service. They’re like little “Energizer bunnies”: they keep concepting and concepting until their brains cramp. This is how they get really good.

When I was younger, I used to flip through the Yellow Pages (remember that?) until I’d find an interesting business, the more obscure the better. Then I’d create a spec ad for that business. Back in the 1980s, when I was just getting started, I wrote a spec-ad for a music teacher who taught the accordion: “I can teach anyone to carry a tune.” Groaner, yes, but the fact is, I practiced my craft even when no one was looking.

If you write creative briefs for a living, can you say the same? If the answer is no, my next question is: Why not?

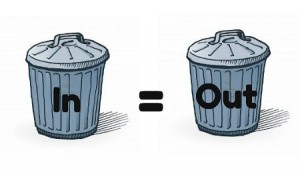

I’ve said it over and over: the creative brief is the first step in the creative process. Get it wrong here and everything that follows suffers proportionately. It’s the principle of “garbage in, garbage out” at work.

Practice is vital.

But who has time to practice?

Professionals do. If you’re a professional, you must practice.

Here are three techniques you can adopt right away.

1. Practice in your head.

One of the more important questions on a creative brief is, “What is the Single-Minded Proposition?” This is something you can practice formulating as you commute to and from work. You don’t even need pen and paper.

Imagine the product or service, conjure its key benefit and translate that benefit into a “What’s in it for me?” proposition that directly addresses the product’s best customer. Think of that short phrase or sentence. Don’t stop there. Think of alternatives. Come up with many SMPs. Which one is the best? Why?

Turn this into a brain-game and repeat it often. It’s called practice. It’s what professionals do.

2. Follow your creatives’ lead: Do spec work for a favorite cause or a pro-bono client. Now you have a reason to practice.

If you don’t do this already, it’s time to start. Most agencies and brands dedicate time and resources to charitable causes. Volunteer. Even pro-bono projects need creative briefs.

3. Start an in-house creative-brief writing workshop whose purpose is honing brief-writing skills. Volunteer to lead it.

The first time I was asked by a dean of student affairs at one of the community colleges where I now teach whether I’d ever taught grammar, I hesitated for just a second before saying yes and accepting the assignment.

In truth, I’d never taught grammar before. But it turned out to be the best and most fun experience I’ve had in the classroom. And I mastered the fundamentals of grammar because…

…I had to teach them!

Whether you’re a 20-year veteran or a newbie, you, too, can teach someone how to write a better brief. When you teach, you become a better practitioner. If you do even rudimentary research online, you’ll find source material that will help you teach brief writing, and my book is only one of them (although I happen to think it’s the best source).

The point is, every brief writer needs practice. No professional doesn’t need practice.

Take the initiative. Start now. Because you’re a professional.