Beginning writers tend to learn a lesson about plagiarism the hard way. They commit it unintentionally. They didn’t mean to quote an author without giving him or her due credit, but…

Unintentional plagiarism, I can attest from years of classroom experience, is the most likely kind of plagiarism a college freshman blunders into. The problem is, it’s still plagiarism and they still fail the paper.

The analogy works for a broken creative brief process. The participants, whether they’re in an ad agency or the marketing department of an advertiser, often have no idea their briefing process is broken. They didn’t mean to mess it up, but they did. Something isn’t right, and they keep chugging along hoping to muddle through.

It’s not unlike the definition of insanity: You keep doing the same thing over and over and hoping for, well, you know the rest.

So how can you tell when your briefing process is broken? What are the red flags?

Look for these four warning signs. In fact, if you recognize even only one of them, it’s time to address your creative briefing process before it does, in fact, break.

You Know It’s Broke When:

1: The people who work from the brief roll their eyes after it’s presented.

That’s an exaggeration. The people who work from the brief, and this is the creative people, are a difficult lot to begin with. They love to complain: about bad briefs, bad coffee, bad shoes. They complain because it’s in their nature. They tend to be jaded and borderline cynical. Okay, forget borderline.

They complain about bad briefs, especially, because they read them so often. They may in fact respond to any brief with an exasperated sigh. It’s reflexive. They can’t help it.

But if this happens frequently and is followed by a rush of questions of a certain nature, you’re in trouble.

These questions tend to look like this:

“I thought you said we couldn’t…”

“Are you sure you mean it this way? Last time you said…”

“Why is this okay now? Last month…”

“But I thought they hated (insert color/celebrity/location/idea)…”

“Wait a minute. That single-minded proposition has two/three/four ideas. Which one do they really mean?”

2: The parties do not agree on content.

You Know It’s Broke #2 is a subset of #1. Even if you can satisfactorily answer all the questions posed by your creatives after the briefing, you may not have a salvageable brief.

Those questions—and the underlying attitude of skepticism—tend not to be addressed to anyone’s satisfaction, and are a symptom of the broken process.

The fundamental premise of the brief comes into question. One of two things can happen.

First, the briefing ends in disagreement and creative go off and write their own brief, even if it’s not a formal document. They devise their own Single-Minded Proposition and that becomes the brief.

Sometimes this actually works. But you won’t know it even happened until the day the work is presented. If the work does not meet expectations, the Creative’s Creative Brief Syndrome is typically to blame (that’s my fancy term for the creative department’s DIY brief. Which you don’t want).

I know. I’ve committed this heresy myself, although only a handful of times. I’d say my batting average was above .500. That’s exemplary if you’re in the Majors. It’s horrible when you bomb in a creative presentation.

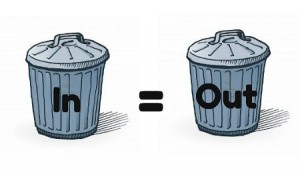

The second scenario, and the more likely outcome, is that the creative team leaves the briefing confused, and that’s what the work looks like when it’s presented. It’s a perfect illustration of “garbage in, garbage out.”

These situations are why I wrote my book on the creative brief. It was the result of feeling utterly frustrated because my creative department operated either without a formal brief altogether, or we functioned with a brief that one or more players did not fully embrace. Any process is only as strong as its weakest link.

3: Only one player in the process writes the creative brief. This situation will almost always guarantee Reasons 1 and 2 above.

You Know It’s Broke #3 stands independent of the first two. It’s a symptom of old-school silo-ing, a tradition that dates back decades.

The creative departments of major ad agencies know first hand about the silo effect. In the 1950s and into the 1960s, most creative departments did not have “teams” of art directors and copywriters. They were separate departments. The did not talk to each other.

Geniuses like Bill Bernbach changed that. Copywriters and art directors were teamed up and expected to work together. The results played a seminal role in producing the Golden Era of advertising in the 1960s.

Account and brand planners have wised up in recent years. They have been moving away from working independently as the owners of the creative brief and have advocated for cross-department collaboration. The principle that works so well in creative departments applies here.

Account and brand planners have wised up in recent years. They have been moving away from working independently as the owners of the creative brief and have advocated for cross-department collaboration. The principle that works so well in creative departments applies here.

If the author of the creative brief in your place of business works alone, even if she works with a partner in the same department, chances are you have a broken creative briefing system, or one that is sick and needs 911.

If creatives have no role in the process, they have little at stake. If they collaborate on not just writing the brief, but then also play a role in briefing on the brief they helped author, things change. Drastically and dramatically.

4. The reviewers of the creative work don’t know how to review the creative work.

The ability to offer clear feedback on the creative work is an absolute job requirement. There is no excuse for being inarticulate or afraid to hurt someone’s feelings.

Rest assured, advertising creatives are professionals. They have thick skin and can take criticism.

Still, being a critic is not easy. It takes finesse, patience and practice. Especially practice.

So I recommend that you practice. A lot. You don’t become adept at writing a creative brief by doing it once. Or even 10 times. You must write them dozens of times and even then you’ll learn something new with each attempt.

Find a piece of creative work not connected to your job or your brand. It could be a TV spot or an email.

Critique it. What do you like? What doesn’t work? Make a list. Write down your thoughts. You don’t have the creative brief against which to judge it, so use your savvy as a consumer. You are, after all, a consumer.

Team up with a creative in your department or at your agency. Work one-on-one with a piece of neutral creative (meaning something neither you nor the creative is connected to) and ask questions about how to review it. Believe me, your creative partner will have some thoughts and won’t be afraid to speak them out loud. This is a learning opportunity for you.

The point is, the only way to become proficient at reviewing creative is to review it.

Remember the old joke: How do you get to Carnegie Hall? Practice, practice, practice.

Step back and ask yourself some tough questions about your creative brief and the process of briefing. If you suspect any one of the symptoms I’ve discussed above, it’s time to reexamine your process.