If you claim that you use a creative brief, yet you ask your creative partners to return four or five times—or more—with revised creative work, do you need me to tell you something is wrong with your creative brief?

Can’t you see the obvious?

This is the classic definition of insanity: doing the same thing over and over, yet expecting different results.

Yet it is a story I hear regularly when I lead workshops on writing the creative brief. It is the most common complaint I hear.

I don’t need to see your creative brief template to know what the problem is. The template is fine. I promise.

Content. The problem lies in your creative brief’s content. You don’t have the right information. Or you have the right information, but it’s buried beneath too much useless, irrelevant information. Or your brief’s content lacks conviction, specificity, clarity. Or all of the above.

The creative brief requires you to put a stake in the ground. It requires you to make choices, to leave out more than you keep. Completing this document requires courage. It is an act of strategic reduction.

It is not a repository of everything you know about your brand. Instead, it is a reliquary of the bold and definitive argument for your brand.

Process. The brief itself may be only part of the reason why there’s a disconnect between a client’s request and delivered creative work. It may also be your creative briefing process. That process breaks down, becomes dysfunctional, if the document does not have advocates from senior management. If the process is not taken seriously, is treated as an afterthought, a necessary evil, you can count on multiple rounds of creative that miss the mark.

A broken creative briefing process is the author of the saying: “There’s never time to do it right. There’s always time to do it over.”

Consider this analogy:

When I played golf a lot, I learned to approach the par-5s backwards. Since I didn’t have the length off the tee to get to a par-5 in two shots, I always planned for a layup. Thus I asked: Where do I want my second shot to be resting? My answer was: about 100 yards from the pin. So if the par-5 were 500 yards, and I wanted my second shot to be sitting at the 400 yard mark, give or take, that meant my drive could be relatively short, say 240 yards. That would leave me with only 160 yards to get to my ideal 100 yard approach shot. (It’s called strategy.)

That is a lot less daunting than trying to boom out a 260 drive followed by a 240 yard approach. On my best day, a “once-in-a-lifetime” series of shots, I might pull that off. I parred a lot of 5s with my less-risky plan. Sometimes, I even birdied.

The point is this: If you don’t have a plan for the time it takes to do your projects, the best creative brief in the world becomes a useless piece of paper. And if the piece of paper doesn’t have the right, agreed upon information, with clear objectives and insights, no schedule will survive it.

To get the best work in the fewest rounds, you must have a plan. You must commit to a creative brief that works within a reproducible creative brief process. The creative brief is Step Number One in the creative process itself.

I would much rather hear a company tell me that they don’t use a creative brief. This, at least, presents an opportunity to inculcate a process that brings all players together around a common purpose: The brand.

When I lead workshops on the creative brief and I see an example of a company’s brief only to discover that it is a rote document with little or no original thinking, no insight, no inspiration, I am not surprised to learn that the creative work falls short. Not occasionally. Not once in a while. Always. Repeatedly.

It usually means a weak or non-existent creative brief process as well. One leads to the other. The two are inter-dependent.

Here, then, is some advice on how to repair or re-invigorate your creative brief and the process you establish:

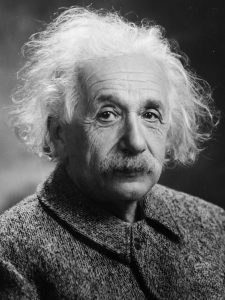

Think misers. Social scientists tell us that we tend to be miserly when we think. Thinking is hard work, even for the likes of Albert Einstein. So we avoid it when it’s not absolutely necessary.

Keep this fact in mind when you approach the creative brief. It is a document, and part of a process, that requires thinking. Serious thinking. The creative brief is part of the creative process, so plan for it. Build enough time into your production schedule so that its writers (more than one) can THINK about it thoroughly.

The creative brief should go through multiple drafts. More thinking! It is not the product of a committee, but rather a dedicated, small group (account, planner, creative), all stakeholders, who weigh in on the effort. One person should do the writing, but the other one or two must be good editors and BS detectors.

In the same way that art directors are paired with copywriters in the creative department, creative briefs should be produced by teams. Who think! Together!

This is current best practices.

No one practices writing the brief. Yeah, it’s a fact. No one writes a brief until they actually have to. Think about that for a second. Imagine if LeBron James didn’t practice a free throw or jump shot until he had to do it in a game.

Uh-huh. We’d have never heard of LeBron James. Like all exceptional athletes, he spends more time practicing than he does playing. He has to. Do you?

You can practice writing briefs without a pen, paper or keyboard. You can do it in your head. You may do it without knowing it. Ever watch a TV spot and wonder what they were thinking? Imagine, if you can, what the brand’s most important message is. Did the spot address it? Why or why not? If not, how would you say it? That’s creative brief-writing practice.

It’s also thinking, and this is where the social scientists’ term “think misers” comes from. You watch the spot, don’t get it, or wonder how they arrived at that idea, then stop thinking. It’s too much work. Besides, your show is back, so you can turn off your brain and just take in the entertainment.

Do it differently next time. Actually THINK about why that spot works or doesn’t work.

This is practice. It’s grooving your swing, so to speak. It’s forging creative-brief muscle memory.

Invite senior management to write a creative brief. Do this collaboratively. Loop them in as early as you can. Ask for suggestions. Give them a firm deadline. Move on if they miss it.

Even if you get a C-level exec to participate only once, you’ll remind them of the value of the process, or clue them into it if they’ve never done it before. This is how you acquire new stakeholders. This is how change happens.

Like all processes, they are slow to become instituted and slow to change. But when you recognize a broken process, address it as soon as possible. Your brand deserves it.